The term 4Cs we know today had its start in the early 1940s, as the brainchild of GIA founder Robert M. Shipley. A former retail jeweler, Shipley was fiercely committed to professionalizing the American jewelry industry. He established an institute (GIA) to provide jewelers with formal training and was a tireless advocate for greater knowledge, ethics and standards when it came to buying and selling gems.

Robert M. Shipley founded the Gemological Institute of America in 1931. Photo: GIA

Shipley developed the 4Cs as a mnemonic device to help his students remember the four factors that characterize a faceted diamond: color, clarity, cut and carat weight. The concept was simple, but revolutionary.

Throughout history, diamond merchants used a variety of different, usually broad, terms to talk about these four factors, rarely with any consistency. Terms such as river or water were used to describe diamonds that were the most colorless, with Cape assigned to pale yellow diamonds from South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope region. To describe clarity, they referred to diamonds as being “without flaws” or “with imperfections.” Cut was described as “made well” or “made poorly.” As a result, it was very difficult for jewelers to communicate those elements of value to their customers or for their customers to remember them. Only the term carat to describe weight has been used consistently from the 1500s to today.

Under Shipley’s direction, the term 4Cs became part of the American gem industry’s vernacular, popularized through advertising campaigns, lectures and GIA education courses. Within decades, they were integrated into the international nomenclature as well.

The 4Cs and the Diamond Grading Scales

Jewelers welcomed Shipley’s innovation, but GIA did not stop there. Shipley’s successor as president, Richard T. Liddicoat (affectionately known as “RTL” by later generations of GIA staff) – along with colleagues Lester Benson, Joseph Phillips, Robert Crowningshield and Bert Krashes – expanded on the 4Cs.

Richard T. Liddicoat, president of GIA from 1952 to 1983, integrated the 4Cs into GIA’s curriculum and laboratory reports. Courtesy: Norman B. Samuels Portrait Photographers, Los Angeles

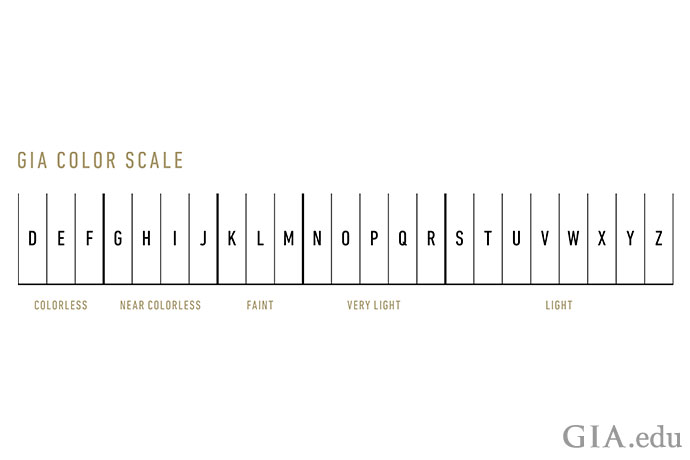

Their work included not only development of the now famous GIA D-to-Z Color Scale and GIA Clarity Scale for diamonds, but also the scientific methods and procedures for objectively grading a diamond’s quality.

A 2.78 carat (ct) D-color round brilliant diamond that is internally flawless is a wonder of nature. GIA invented the color- and clarity-grading terminology that is now used internationally to describe diamond quality. Photo: Robert Weldon/GIA. Courtesy: Rogel & Co. Inc.

Color: The GIA D-to-Z Color Scale

Before the 4Cs and RTL’s contributions, a confusing alphabet soup was used to describe a diamond’s color. In communicating color quality to consumers, retailers used competing systems with descriptors like “A,” “AA” and “AAA.” There was virtually no agreement among firms as to what was considered an “A” grade. Most diamond wholesalers used terms like rarest white and top Wesselton, in addition to those mentioned above. In short, there were no standards that allowed for consistent evaluation and comparison.

Since the 1930s, GIA had been working on an accurate, objective color-grading system for colorless to light yellow diamonds. The goal was to develop a system based on absolutes, instead of relative terms and vague descriptions. In 1953, GIA, under RTL’s direction, introduced the GIA D-to-Z color scale, choosing the letter “D” for the top grade (colorless) precisely because the letter had negative associations and so was unlikely to be misinterpreted or misused.

GIA’s D-to-Z Color Scale is the industry standard for grading the color of colorless to light yellow diamonds.

In addition to establishing a color scale, RTL and his colleagues defined the methods that would be used to grade a diamond’s color accurately and consistently. These included determining the type of lighting and neutral background with which a diamond should be evaluated, prescribing precisely how the diamond should be held and viewed, and developing master stones: sets of diamonds of predetermined color value against which the subject diamond is carefully compared.

The D-to-Z diamond color terminology RTL and his colleagues pioneered is now used around the world, and strict color-grading procedures are followed by the GIA laboratory.

Understanding the 4Cs is essential if you’re shopping for a diamond engagement ring. This one has a 1 ct center stone surrounded by four diamond side stones. Melee diamonds in a halo setting frame the design and continue down the shoulders of the ring. Courtesy: Sylvie Collection

The GIA Clarity Scale contains 11 grades that range from Flawless (FL) to Included (I3).

Clarity: The GIA Diamond Clarity Scale – Flawless to I3

Diamond clarity grading was another area that was plagued by inconsistencies in terminology and methods. Some trade professionals used terms like perfect in addition to without flaws and with imperfections, which were vague and imprecise. Others used terms we recognize today, such as VS, VVS, and included, but without any agreed-upon definitions. RTL and Benson used these terms in creating a clarity-grading scale, but defined precise categories and expanded the number of grades within each category to account for the array of diamonds in the market. Fine-tuned in subsequent years, the GIA Clarity Scale today consists of six categories ranging from Flawless to Included and contains 11 specific grades.

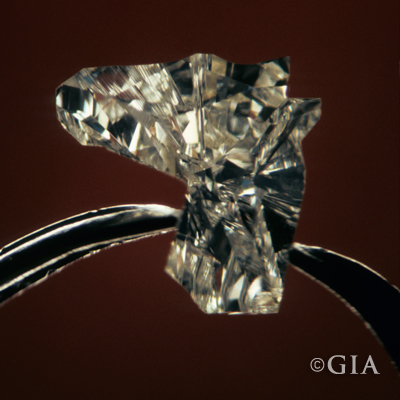

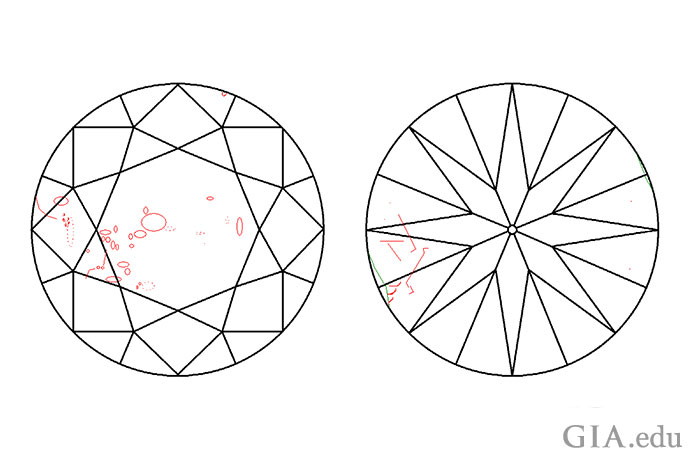

This precision in clarity grading was made possible by another GIA innovation: the introduction of the gemological microscope as a tool for clarity grading. Using the microscope, GIA graders plot the inclusions and blemishes in all diamonds for which a full GIA Diamond Grading Report has been requested.

A plotting diagram, a feature of all GIA Diamond Grading Reports, uses specific symbols to map a diamond’s various inclusions and blemishes.

Cut: Evaluating a Diamond’s Interaction with Light

The impact of Cut – how well a diamond interacts with light – was another attribute that RTL and his associates wanted to better explain and standardize. Originally, RTL turned to the work of Belgian mathematician and diamond cutter Marcel Tolkowsky to help determine “ideal” proportions for a round brilliant cut diamond. RTL’s contribution included a rating system with deductions for proportions that deviated from those.

Because of GIA’s efforts to standardize the evaluation of diamond cut, round brilliants such as these can now be objectively graded. Courtesy: Supreme Jewelry

GIA’s system for evaluating cut has been modified over the decades. In 2006, after years of extensive research that included advanced computer modeling and observational studies, GIA introduced the GIA cut grading system for round brilliant cut diamonds. Today, the GIA Cut Scale, ranging from Excellent to Poor, describes how successfully a diamond interacts with light to deliver the brightness, fire and scintillation we associate with a fine round brilliant.

The GIA Cut Scale assesses the overall cut quality of each diamond individually, taking into account such features as proportions, table size, polish and symmetry.

Many factors contribute to the evaluation of a diamond’s cut, including the size of the facets, girdle thickness and total depth.

More than the 4Cs: The World Standard

Using the latest scientific advances to establish grading standards that provide consistent, repeatable results, GIA has revolutionized the jewelry industry. With the framework provided by the 4Cs, it has transformed the way diamond quality is determined and communicated and, ultimately, how diamonds are bought and sold.

These standards are strictly followed by the GIA laboratory in its nine locations worldwide. They allow GIA to deliver objective, consistent diamond grading results anywhere in the world. It is important to note that although the terminology introduced by GIA has been adopted by other laboratories worldwide, only the GIA laboratory has the proprietary equipment and procedures to grade diamonds to these standards.

All this critical information becomes part of a GIA Diamond Grading Report. With it, you’ll know the essential facts about the diamond you’re considering.

The GIA Diamond Grading System provides a complete description of diamonds such as this 1.37 ct H-color, VS1-clarity round brilliant in a platinum Tiffany & Co. setting. Courtesy: 1stdibs.com

Why ask for a GIA Diamond Grading Report? Read more and decide for yourself.