It’s a pleasant September morning in the year 1622 and a majestic Spanish galleon sits in the port of Havana, along with 27 other ships of the combined fleet, their crews awaiting orders.

The Nuestra Señora de Atocha sits low in the water, weighed down by 964 silver bars, 161 gold bars or disks, 255,000 silver coins, and uncounted chests filled with undeclared (and untaxed) emeralds. Smugglers be warned: punishment is 200 lashes and ten years spent in chains, rowing a galleon.

The Atocha, a 20-cannon, 500-ton colossus, is the rear guard of the fleet. Its job is to protect the smaller and slower moving vessels from pirates and Dutch warships that are ready to seize the booty in Holland’s war with Spain. Some of the most valuable cargo, as well as a company of infantrymen to protect it, and its crew and passengers are packed into the galleon, ready to return to Spain.

Much depends on the arrival of this floating caravan. Spain is on the edge of bankruptcy: financing wars, the lavish spending habits of King Phillip IV and his court, and defending the far-flung empire, have emptied the royal coffers. The Atocha and the other ships will carry the gold and silver to Spain so the king can pay his creditors and prop up the teetering economy.

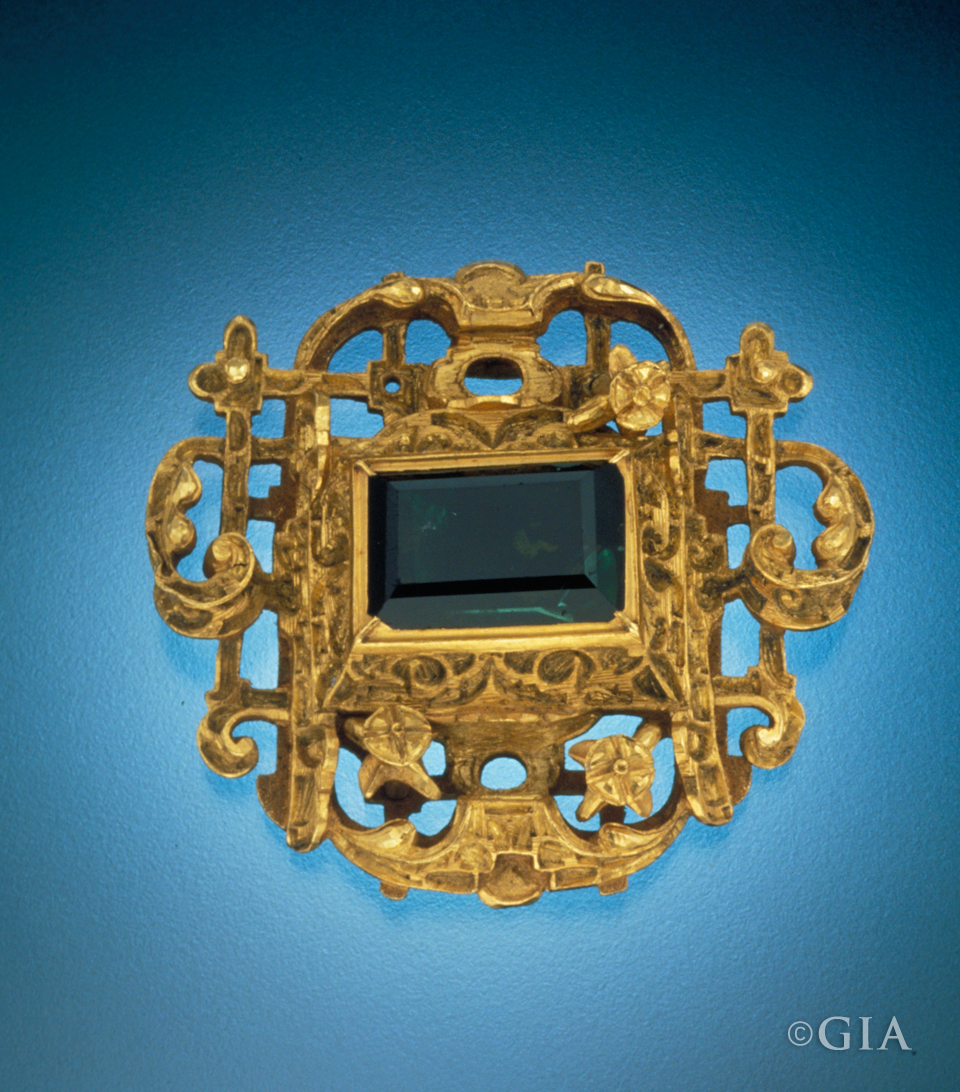

Some of the treasures of the Atocha: a gold rosary with an emerald cross, two emerald rings, an emerald brooch, a gold chain, and loose uncut Colombian emeralds. Photo by Shane F. McClure/GIA.

The ships should have sailed weeks earlier, but had to wait for silver and other valuable goods to arrive from Peru. Now the fleet will be beginning its journey at the start of hurricane season.

Fleet officials debate if it is still safe for the ships to set sail. The decision is a difficult one. If the fleet does not leave for Spain, the ships will stay docked for months, which might be ruinous for king and country – and costly to the merchants and their idle cargo. Urgency trumps caution, and the fleet departs for home.

After just one day on the open seas, the decision to set sail will prove to be a historic disaster.

The riches of the New World on display: A gold chain and emeralds from the Atocha. Photo by Shane F. McClure/GIA.

On the morning of September 5th, high seas and ferocious winds lash the Atocha and the other ships. The fleet has sailed into a hurricane, and by nightfall, the stormy seas claim several ships. On the second day, the Atocha, rudderless and without its foremast, helplessly careens towards a reef along the Florida Keys. A massive wave smashes it against the rocks and drags it to the bottom. Of the 265 people on board, five survive.

Retrieving the lost riches of the Atocha and the Santa Margarita is so important that a salvage effort is immediately ordered. Some of the cargo from the Santa Margarita was recovered but Mother Nature intervenes: Two more hurricanes strike, and the Atocha and her riches are scattered across the ocean floor. After 60 more years of searching, the Atocha and the other ships are declared lost.

* * *

We jump forward to 1970. American treasure hunter Mel Fisher has an audacious idea: he will find the legendary Atocha and recover its treasure. Piecing together historical accounts, and chasing rumors, Fisher spends 16 years scouring the seafloor between the Florida Keys and Dry Tortugas. Discoveries come in tantalizing bits and pieces: an anchor in 1971; 4,000 silver coins in 1973; five cannons in 1975. Finally, on July 20, 1985, Fisher’s team finds the Atocha.

The recovered treasure is more than 40 tons of gold and silver, including more than 185,000 silver coins, and Colombian emeralds.

* * *

In 1988, GIA examined and reported on seven rough emerald crystals, an emerald and gold rosary, two rings, a brooch, and other items from the Atocha. The seven rough emeralds and the mounted emerald had the characteristics of Colombian emeralds, specifically the presences of three-phase inclusions (internal clarity characteristics that have a solid, a gas bubble, and liquid). GIA described the emeralds as transparent to translucent and from medium to dark tones of green to slightly bluish green. The gemologists believe that a fine precipitate of seawater may have seeped into surface breaking fractures in the emeralds, causing a chalky yellow-green fluorescence.

A few pieces of jewelry recovered during salvage operations and seen by GIA include an emerald brooch that was determined to be slightly less than 24K gold with a deep yellow color. The rosary consists of an ornately carved cross set with nine cabochon emeralds, and prayer beads (possibly made out of wood) that disintegrated but the gold bell caps remain. The gold chain, one of many recovered from the wrecks, shows draw lines on its links. It is thought that gold was worn as jewelry to avoid taxation; when needed, individual links could be removed from the chain and used as currency. A spoon with an intricately carved handle showed spectacular craftsmanship was also examined.

A cross set with emerald cabochons was one of the treasures brought up from the sunken Nuestra Señora de Atocha. Photo by Shane F. McClure/GIA.

The sinking of the Atocha hastened imperial Spain’s decline as a world power, but it also was an archeological and gemological time capsule. Its recovery provided gemologists and historians with a unique window into this colorful time.

Thirsty for more information about emeralds? Visit the GIA Gem Encyclopedia.

Main image © Shane F. McClure/GIA.

Custom Field: Array