What could impressionist painter Claude Monet and GIA colored diamond graders possibly have in common? For both the artist and the gemologist, the study of how light alters the appearance of an object was, and remains, an important part of their process.

Monet was fascinated by the effect that light could have on an object’s appearance. The painter chronicled the play of light in his famous haystacks paintings but perhaps the most well-known example is a series of paintings of Rouen Cathedral, which shows how changing sunlight alters the appearance of the church’s façade.

Top left: Rouen Cathedral, West Façade, Sunlight, 1894, Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. Top right: Rouen Cathedral, Morning Sun, Blue Harmony. 1893, Courtesy of Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY. Bottom Left: The Portal of Rouen Cathedral in Morning Light, 1894, Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program. Bottom right: Rouen Cathedral, The Portal. Grey Weather, Grey Harmony, 1892, Courtesy of Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY.

Like Monet, GIA researchers understood the effect that light had on the appearance of an object. They knew that inconsistent or changing light sources would affect the appearance of colored diamonds (or any gem material). Since the description of a colored diamond’s color can affect its value, GIA researchers knew they had to find a standard light source for objective observation. This would allow graders to describe the face-up color of the diamond in a repeatable and consistent manner.

Master painters like Monet knew that north daylight was the traditional choice for painting because it does not wash out colors or create fleeting contrasts. North daylight is ideal for seeing the true hues of paint. As it turns out, it is also the best light for grading colored diamonds.

When GIA researchers searched for a light source that would closely simulate north daylight, they found it in a device that creates a neutral standardized viewing environment with color-balanced lighting. This controlled lighting environment allows graders to see the true color and secondary hues of a diamond.

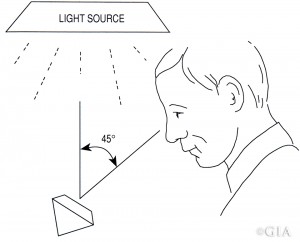

GIA researchers also understood that a colored diamond’s face-up appearance could be affected by how it was held and by materials that came in contact with it during color grading – like tweezers and trays. These variables could cause “color pollution” by adding hues that really weren’t a part of the colored diamond. After considerable experimentation with tweezers, metal stone holders and white plastic trays, GIA researchers found ways to eliminate this problem utilizing a grooved, matte-white, plastic tray; looking at the diamond face-up; placing the light source directly above the diamond; and other methods.

GIA researchers also understood that a colored diamond’s face-up appearance could be affected by how it was held and by materials that came in contact with it during color grading – like tweezers and trays. These variables could cause “color pollution” by adding hues that really weren’t a part of the colored diamond. After considerable experimentation with tweezers, metal stone holders and white plastic trays, GIA researchers found ways to eliminate this problem utilizing a grooved, matte-white, plastic tray; looking at the diamond face-up; placing the light source directly above the diamond; and other methods.

Using a standardized viewing geometry, a trained grader can readily see and evaluate a faceted diamond’s face-up color.

Monet’s paintings, like those of the Rouen cathedral, celebrate light’s ability to alter our perception of objects. GIA researchers, on the other hand, sought to control light’s changing effects by creating consistent, reproducible conditions simulating north daylight to help standardize the appearance of color. The end result benefits colored diamond enthusiasts everywhere.

Custom Field: Array